[a look back] Ten Years of Naatak: Bringing Indian Theater to the Bay Area

TEN YEARS OF NAATAK

Bringing Indian Theater to the Bay Area

by Sujit Saraf

Ten years ago, seven people met at the International House of the University of Berkeley, writes Sujit Saraf, who helped found NAATAK, which celebrates 10 years this December with its 22nd production. In the intervening years it has produced plays in Hindi, Tamil and English as well several films.

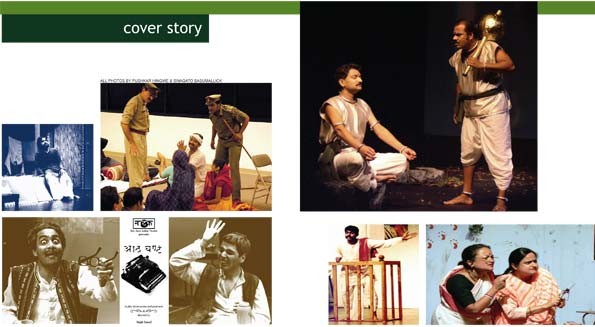

Scenes from NAATAK plays: Clockwise from top left: Sujit Saraf in Mohan Rakesh’s “Aashaadh Kaa Ek Din” (Apr 1998); Vijay Rajvaidya, Monica Mehta Chitkara, Harish Sunderam Agastya, Shobhna Upadhyay and Navjoti Sharma in Bhisham Sahni’s “Muavazey” (Nov 2004); Harish Sunderam Agastya and Aniruddha Bhosekar in Sujit Saraf’s “Tathaa Kuru” (Feb 2004); Ranjita Chakraborty and Monica Mehta Chitkara in Jaywant Dalvi’s “Arey Shareef Log” (Jun 2005); Parthasarathy Mamidipudi in Vijay Tendulkar’s “Khaamosh! Adaalat Jaarii Hai” (Feb 1996); Rajiv Nema (left) and Alok Kuchlous (right) in Sujit Saraf’s “Aath Ghante” (Feb 1997).

NAATAK began in the fall of 1995, when a friend and I started looking for ways to indulge our love of theater. We had fond memories of plays we had staged while in college, and we wondered if it was possible to re-create those days. The Bay Area was home to many community organizations and cultural festivals, but we found no group focused entirely on theater, on the reading and staging of full-length plays. It became obvious that if we were to regularly participate in plays, we would have to start our own theater group.

We decided that the most efficient manner of creating a theater group was to simply stage a play, and hope that the group would form itself around the event. So, instead of announcing the formation of NAATAK, we announced an audition for Vijay Tendulkar’s Khaamosh! Adaalat Jaarii Hai. We sent out emails, posted notices on newsgroups, and hoped for the best. On December 2, 1995, seven people collected in a lounge in International House, my dormitory at Berkeley. We read the entire play, slowly, over four hours. In the next audition, held the next day, we attracted a few more people, and I assigned roles. We were unable to find a full cast through our auditions. We also had no idea how many people would come to watch our play, and we did not yet have a theater. We began rehearsing anyway, and I soon became aware of the challenges we faced. Although most of my actors could speak Hindi fluently, none had read Hindi in the last few years, so they struggled with the script. Then there were the complications of transport and scheduling. Half my cast lived in the South Bay, and the other half in Berkeley. Those in the South Bay were engineers available only on evenings and weekends. Those in Berkeley, including myself, were graduate students without cars. To distribute the inconvenience, we split our rehearsals between the Berkeley and Stanford campuses. Much time was spent on BART trains, getting picked up and dropped off at BART stations, fixing rehearsal times, adjusting those times to accommodate project deadlines, exams, quizzes and semesters. After a few chaotic weekends, we were able to find an opening at Cubberley Theater on February 16, available only because that was President’s Day weekend. We simplified our sets to wooden frames covered with cardboard, and one of my actors manufactured them in his apartment in Berkeley. We varnished and painted the frames together. Through a combination of spamming and cajolement, we were able to sell eighty tickets in advance. On February 16, I was pleased to see a modest queue form at the box office. We staged Khaamosh! Adaalat Jaarii Hai. Two hundred and five people watched the play, and NAATAK was born.

Ten years later, we will stage our twenty second production in December. We have produced three films and eighteen plays in Hindi, Tamil and English, entertaining an ever-growing audience of theater lovers in the San Francisco area. As it happens, our twenty second production opens on December 2, exactly ten years after that first audition. Much has happened in the last ten years around us, including the boom and bust in Silicon Valley. Our members, most of whom are professionals in the software industry, have prospered and suffered with the boom, but NAATAK has somehow continued to grow. Membership is free and informal. All auditions are open to the public. Anyone who has participated significantly in one NAATAK production and has a good script is eligible to produce or direct a play after committing to abide by NAATAK principles in good faith. This has created a large pool of directors, actors, set-designers, make-up artists, sound and light experts, publicity and marketing teams, which NAATAK draws upon for every subsequent production.

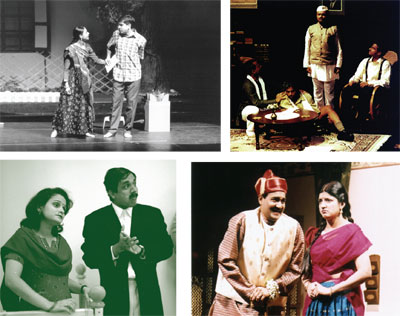

(Clockwise from top left) Divya Jain and Amit Garg in Dharamvir Bharti’s “Suuraj Kaa Saatwaan Ghodaa” (Feb 2003), adapted for the stage by Vipul Srivastava; Rajiv Nema and Pritha Chatterjee in Vasant Kanetkar’s “Kasturi Mrig” (Dec 2003); Brajesh Upadhyay, Aniruddha Bhosekar, Amit Nanavati and Abhijit Chakankar in Sujit Saraf’s “Vande Maataram” (Aug 1998) and Anshu Johri and Sujit Saraf in Vijay Tendulkar’s “Khaamosh! Adaalat Jaarii Hai” (Nov 2002)

When NAATAK began, I was conscious of the legacy of our theater days in Delhi, where we usually staged British and American plays, such as John Mortimer’s The Dock Brief, Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and Sam Shepard’s True West. There are many reasons, not all defensible, why theater groups in India insist on staging plays they cannot identify with, but I was certain I did not want to repeat those mistakes in selecting plays for NAATAK. Now that I was actually living in the West, it seemed silly to try and penetrate the mind of Tennessee Williams. How could I stand on stage and pretend to be Stanley Kowalski, when someone in my audience might actually have grown up in the French Quarter in New Orleans? It was one thing to play at being Stanley Kowalski in far-removed Delhi and quite another to do so in Palo Alto, among those who certainly knew better. We decided, therefore, to stick to plays by Indian playwrights.

(Above) Ram Padmanabhan and Mark D. Hines in Mahesh Umasankar’s short film “The Seine.” (May 2005); (Below) Navneeth Rao in Sujit Saraf’s full-length feature film “Asphyxiating Uma” (Mar 2002). NAATAK’s first film was “Bugaboo” (Jul 1999), a quirky, full-length feature film on the foibles of desi Silicon Valley techies.

This was easier said than done. There is a dearth of good theater scripts in Indian languages, especially in Hindi. Indeed, many good Hindi plays are translations from Marathi or Bengali. Also, the same reasons that kept us away from Tennessee Williams also put many Indian scripts beyond our reach, because the characters in those stories lived in an environment too far removed from ours. Our own life experiences lay somewhere between the Indian-ness of a Sageena Mahato and the American-ness of a Willy Loman. Were there any scripts at all that we could call our own? Over the years, we tried to find these “middle scripts” and imagine the lives of their characters. Sometimes we hit the right combination, sometimes we did not. When we found no scripts, we wrote our own. Our upcoming production in December, Everyone Loves A Good Tsunami, is in fact our own script, set in the Bay Area among people we understand very well.

This distance from our stage characters often extends to our audience which, after all, is the very pool from which NAATAK actors are drawn. I remember the first ten seconds of our first play, Khaamosh! Adaalat Jaarii Hai. The play begins with the entry of Samant, a villager, and Leela Benare, an actress in a visiting drama troupe from Bombay. “This is the hall where your play will be staged,” says Samant as he enters the stage wearing a kurta and a dhoti. As soon as Samant said this, the audience began to laugh. Standing backstage, I was puzzled. Why were they laughing? What was funny? Had Samant’s dhoti slipped off his waist? Had Leela Benare stumbled? Had we already doomed our theater group in its first few seconds? But of course, none of these things had happened, and our audience had not laughed in derision. They were merely amused to see a man wearing a dhoti, they were pleased to hear Hindi spoken on stage, and they were tickled at the sheer improbability of watching a Hindi play in Palo Alto. The experience was novel, so they expressed their approval with laughter. While these were reactions I may have expected, they had nothing to do with the play. They superseded the play and defeated its purpose, at least in that one opening scene. I was disappointed. It appeared that, just because we had staged a Hindi play in Palo Alto and reminded everyone of home, they were prepared to say it was a “great show”, regardless of the quality of our performance. All that was expected of us was the soft scent of nostalgia. How would we ever stage a good play?

Fortunately, this was not entirely true. One cannot expect novelty to entertain an audience for two hours, as was proved by the emails, several critical, that I later received. I now realize that we were fortunate. We were not, and still aren’t, professional theater artists. We are engineers and homemakers who love theater, watch plays and stage them. Over the years, we have acquired many of the skills that professionals might possess, but perhaps not to the same degree as people who do this for a living. We have learned a lot on the job, but if our audience had not been forgiving while we learned, we may never have found the will to continue. After ten years, no one finds it amusing merely to be watching a Hindi or Tamil play. No one thinks it funny when a man walks out on stage wearing a dhoti. Our audience expects a full-blown play and is quick to criticize. There are now many more theater groups dedicated to producing good theater, and we are much more confident in our ability to stage elaborate productions. The same non-professional status that undermines our dedication to theater also frees us from the constraints that usually bind a professional theater group. Because NAATAK members do not depend on theater for their livelihood, we are able to select plays that we really like, and stage those plays exactly as we prefer. We are able to remain faithful to our central goal of producing intelligent, thought-provoking plays, and doing so in a tasteful manner. At NAATAK performances, there are no promotional gimmicks, no elaborate speeches, no chief guests, no sponsorships, no banners, no announcements and no exhortations to buy anything. Every show begins with a short introduction to the play, usually offered by the director or producer. Although most NAATAK profits have been given away to other non-profit organizations, the audience is not subjected to a harangue about proceeds going to this charity or that, on the assumption that people come to watch a play on the merits of the play, not the cause it indirectly supports.

As befits a theater and film group, NAATAK is celebrating its tenth anniversary by staging plays and producing films. The Seine, a film directed by Mahesh Umasankar, premiered in June this year, followed by Jaywant Dalvi’s hilarious play Arey Shareef Log, directed by Rajiv Nema, which concluded a very successful run in Palo Alto and Hayward in June and July. The celebration will be completed by Sujit Saraf’s Everyone Loves A Good Tsunami, an irreverent look at the fund-raising fever in America, which will be staged in December.

NAATAK has grown organically in the last ten years. More than two hundred people have participated in our plays and films. Our vision for the next ten years is that Indian theater will become a regular part of life in the San Francisco area. People will say over dinner,“Let us go and watch a NAATAK play”, just as they go and watch films. Instead of being a rare and occasional indulgence, “going to the theater” will become a common form of entertainment, to be enjoyed with discrimination and taste. And, through it all, NAATAK hopes to continue staging mature, creative plays, again and again, without much fanfare, but with great artistry and craftsmanship.

Information on NAATAK auditions, play readings and future productions can be found at http://www.naatak.org.

Sujit Saraf is a writer, theatre activist and a software engineer.

He lives in San Jose, Calif