Shatranj Ke Khiladi – Bringing Awadh Alive

Shatranj ke Khiladi is a brilliant socio-political satire by Munshi Prem Chand that has been adapted for stage by Naatak in this 2023 production. Set in the 1850s, the plot showcases an indifferent and decadent aristocracy against the backdrop of the annexation of Awadh by the British Army. Awadh was annexed from Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (30 July 1822 – 1 September 1887), the eleventh and last King of Awadh, who ruled for 9 years from 1847 to 1856. Painted by Britishers as an incompetent ruler, the controversial and complex Nawab, however, was a man of many talents.

The Nawab fostered the Ganga Jamuni culture of Awadh. He was an accomplished poet who popularized Thumri and penned over 40 books in Urdu, Hindi and Persian. The Nawab can be credited for the revival of Kathak as a major form of classical Indian dance as well as for being the first playwright of Hindustani Theatre. He spent lakhs of rupees in staging his lyrical compositions or Rahas (a Persianised word for Raasleela) and paid incredible attention to costumes, jewelry and stagecraft. His exile to Kolkata post the annexation made the city a flourishing musical capital which heightened art appreciation and art patronage in the Bengali society.

Eventually as the Hindi Film industry was established in the early 1900s, many Bengali artistes that benefited from such art patronage, went on to make a significant contribution with song, dance and music. Wajid Ali Shah’s Bhairavi Thumri “Babul Mora”, a lament for his beloved Lucknow, was made popular by K.L Saigal’s rendition in the movie Street Singer (1938). It was featured yet again in the movie Qala (2022) which reflects Nawab’s lasting legacy for the industry.

Given the legacy of the Nawab across multiple art forms, it was a daunting task for Naatak to bring alive Wajid Ali Shah’s Awadh on stage. To help the audience travel back in time the language, style of music and dance, sets, costumes and props, all had to reflect the 1850s Nawabi era. Creating a true visual image of Awadh required thorough research and execution – a journey that lasted roughly 6 months for production teams handling sets, costumes and props.

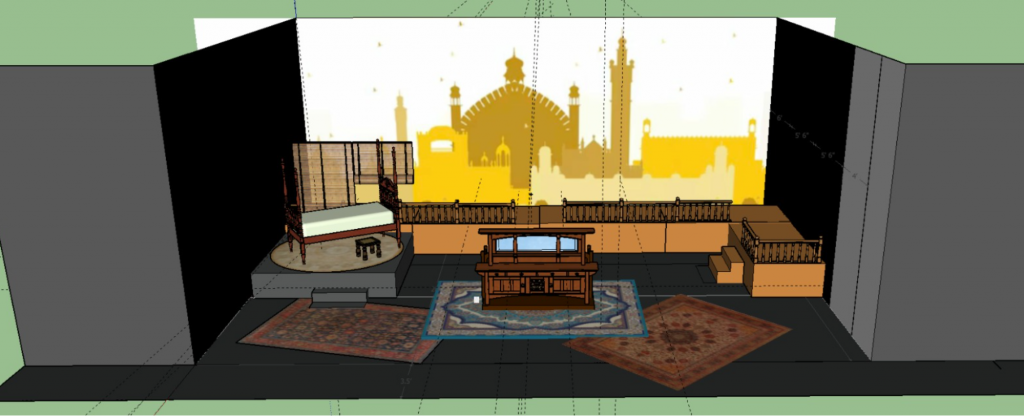

Set Design Diagram – Awadh skyline; Palace railing; Indo-persian carpets rotating diwan and Victorian Colonial Era Bed

The first element of the time capsule would be the sets. Awadh was known for its architectural beauty and the region’s skyline was dotted with ornate arches, bulbous domes and slender minarets. The sets team tried to capture this skyline as the backdrop for the stage. This was further layered with a railing aping the Kaiserbagh Palace courtyard. The checkered flooring across the stage is reminiscent of the ancient style of tile installation found in palaces. Additionally, carpet weaving thrived under the Mughal influence. Hence the floors are bedecked with floral indo-persian carpets.

The heritage homes and palaces of erstwhile Lucknow are abound with antique hardwood furniture.Thus, the audience can see a hardwood diwan (akin to daybed) decorated with rich velvet cover with bolsters in silk and brocade. This piece of furniture is built to be rotatable as well as movable. The back of the diwan is an ornate cabinet embellished with decorative hand painted gold motifs. This rotatable diwan allows the sets team to switch between Wajid Ali’s Palace interiors and living rooms of the affluent from Awadh.

In addition to the living room, the bedroom has also been created on a raised platform with a 4 poster bed resembling the Victorian colonial raj beds. This bed is styled with a brocade patchwork quilt. The sets team also incorporated elements of the Victorian study for General James Outram. The audience will see a large hardwood desk with an upholstered chair and the desk is styled to be inline with the Victorian era.

Left to Right Tailors(India)- Raghvendra Gautam on Men’s Costumes; Shareeq Beig on Women’s Costumes;Sangeeta Vishwakarma on Sepoy costumes and Shawls

Next, let’s go over the appearance of people who inhabit these spaces or the detailed costuming. For generations, Awadh nobility struck a fine figure in expensive silks and fashionable garments. Indian textiles and ornamentation received tremendous patronage and prospered under the Nawabi rule. In order to showcase the apt fashion and craftsmanship of the 1850s for the play, the costumes team at Naatak took the decision to get the costumes tailored in Bhopal, a city that shares the Islamic influence with Lucknow. Lucknowi tailoring excelled in creating various styles of chogas, angrakhas, achkans, sherwanis, kurta pyjama, ghararas and shararas. There is a place for Farshi Gararas and Shararas in women’s bridal fashion even today, however, men’s fashion has indeed changed over the course of years. This proved to be challenging as the tailors required a lot of guidance in order to create the angrakha and sherwani designs which were popular in the 1850s.

To stay true to the era, the costumes are made of rich jewel tone brocade and Makhmal (velvet) fabric with Zardosi laces. The actors are shown donning Jamavar woolen shawls as well as velvet shawls with Gota Patti work. Headdress held great importance, hence Nukkadar caps (pointed caps) as well as round caps with threadwork serve as accessories. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah also invented a hat called Alampasand and the actor can be seen sporting it in one of the scenes. For women’s costumes, the Gharara pyjama are adorned with the modified Tukri or Chatta Patti work – a labor intensive craft from Lucknow. The women are also shown wearing the traditional jewelry like passa, chandbali, haath phool besides layered necklaces which have made a comeback.

Left to Right – Men’s Brocade Sherwani with zardosi Lace; Men’s Brocade Angrakha with zardosi lace; Women’s Brocade Gharara with modified Chatta Patti on pyjama

Left to Right – Men’s Brocade Sherwani with zardosi Lace; Men’s Brocade Angrakha with zardosi lace; Women’s Brocade Gharara with modified Chatta Patti on pyjama

A lot was stated about Nawabi fashion, however the Costumes team also tried to showcase the Victorian era of fashion through men’s frock coats, ascots and brooches and women’s dresses, capes and bonnets. The designs of military costumes for sepoys are inspired by East India Company’s Bengal Native Infantry Unit from the 1800s. A sizable number of recruits to this Unit were from Awadh. General James Outram’s costume bears resemblance to Victorian General’s uniforms as well as latest designs from Firmin & Sons (The uniform maker for British Military since centuries). To complete the look, the costumes are accentuated by the stage decor or props which are in line with the era.

Actors using hookahs; Sharbat glasses and jugs; Paan Dan (brass box) and Hand made Chess set. Actors seen wearing round caps, servant hats and Jamavar shawls.

Tobacco smoking was widely prevalent in 19th century India, be it the hookah (instrument used to smoke tobacco through filtered water), or the chillum (straight conical smoking pipe). The hookah which originated in the Mughal courts, gained significant popularity in the Nawabi era and was considered a status symbol in elite households. Additionally, Moradabad brass industry reached its peak in the 19th century under the Nawabi Era. It ensured a steady supply of artifacts including ornate hookahs that adorned the homes in Awadh. Hence the props team at Naatak carefully researched and procured intricate brass items from India such as the hookahs, paan daan, khaas daan, and sharbat glasses, to align with the 19th century look. A key challenge for the team was to amalgamate the indigenous decor with that of the Victorian British era. The audience will notice the subtle elements of the Victorian influence through use of walking canes, hand-made leather bound books as well as items such as dip pens, quills and scrolls that adorn the desk of General James Outram. Also, the actors can be seen using props resembling the Nawabi swords along with rifles like the infamous Enfield rifle of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857.

Perhaps, the most interesting differentiator is the game of chess itself. While Shatranj or chess owes its origins to India, the game as we know it today with black and white squares on its board, didn’t quite exist in 19th century India. Chess coins were bigger, made of wood with intricate designs and glazed. Chess boards were beautifully decorated and embellished with precious stones. They boasted of a golden ivory and maroon patterning, in line with the coins. The chess boards used in our presentation have been specially designed and hand built for the stage to recreate the Awadh experience. This concludes the arduous journey undertaken by Naatak in order to display the grandeur of the bygone era of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. It is our sincere hope to provide an immersive experience to our audience. Meander through the music filled hallways of Kaiserbagh palace. Peep into the ostentatious abodes of nobility. Laugh at the antics of flawed aristocrats dressed in their finery. Witness the paan and hookah filled gatherings over endless chess matches with side conversations on cock-fights. And lastly flinch at the machinations of the British Army supported by the aristocracy’s indifference to impending doom. _Toh janab zara muskuraiye, aap Awadh main hain! We welcome one and all to watch Shatranj ke Khiladi!

— Namita Chaubal and Anitha Dixit on behalf of Naatak Production Team.