Designing VRINDAVAN

September 28, 2015 Snigdha Jain / Vrindavan

Snigdha Jain

Production Designer, Naatak

Mounds of brightly colored fine sawdust, rows upon rows of makeshift stalls selling clay toys and dolls — Krishnas, Radhas, gopis, dancers, musicians, animals and birds, and jostling crowds, the scene at Burra Bazaar in Calcutta was a sight to behold on the morning of Krishna Janmashthami, the birthday of Krishna. I would look forward to this day all year, Janmashthami being my favorite festival. One big reason was the creation of the Jhanki, a diorama of sorts, depicting scenes from the life of Krishna. Papa would take us shopping in the morning and we would come back home loaded with supplies and clay toys.

At home, Mom would bring down the old cracked leather suitcase from the loft, and we would unwrap the beautiful intricate jhoola (swing), made of colored glass and mirrors. Assorted clay figurines from previous years would also emerge. One of the rooms was cleared of all furniture, the red oxide floor throughly washed and swept, a blank canvas made ready for us. We would make a large colorful carpet-like rangoli using the brilliant pinks, purples, golds, scarlets, blues and emeralds of the sawdust. On top of this, the toys and figures would be arranged gingerly. We created vignettes from Krishna’s childhood in Vrindavan and Gokul – Muralidhar playing his flute with Radha, the gopis dancing around them, a chubby Makhan Chor stealing butter from the neighbor’s pots, Gopala the cowherd, with his beloved gaiyas in one corner, Keshava perched victoriously on the head of the mighty serpent Kalia in another. The jhoola took pride of place in the center, with the Laddoo Gopal installed inside, dressed in his birthday finery, the new outfit and jewelry a gift from my Nani (maternal grandmother). Come midnight, we would celebrate the birth, pulling the cord to swing the baby Krishna in his jhoola strung with strands of fragrant jasmine, singing the aarti and the birthday song:

Nand ke anand bhayo, jai Kanhaiya Lal ki

Haathi lao, ghoda lao, aur lao palki

(Nand is joyous at the birth of Kanhaiya

Bring the elephants, the horses, and bring the palanquin)

When we were younger, Papa used to design and build the Jhanki, and we would proudly help, placing a figure here, straightening a crooked line of sawdust there. The earliest one I remember had a jail made from coals, which imprisoned Vasudev and Devaki at the time of Krishna’s birth. The river Yamuna, that Vasudev crossed to carry the newborn Krishna to safety in Gokul, snaked its way across the floor. As I grew older, I took over the creation of the Jhanki, with my siblings helping. We spent many blissful hours building, bickering, admiring our work.

These are memories of a seemingly distant past. Imagine my delight when Sujit tells me he is writing Vrindavan. Here is a chance to recreate Vrindavan again, on stage, on a much larger scale. As the production designer, I create the visual design of a play – concept, color palette, detailed scenic design and inputs for props, costumes, makeup and lights. We have a very talented team that brings each aspect to life. We start with the script of course, a beautiful story of 12 Vrindavan widows, interspersed with Meera bhajans. Sujit wants a space where the widows live, eat, sleep, but with interesting ways to showcase them across the stage. We need spaces for the musicians and the Kathak dancers to perform.

First comes the quick paper sketch, I draw a set of interconnected buildings with lots of doors and archways, windows, domes and staircases, inspired by pictures of the buildings and temples on the Vrindavan ghats. This is a dynamic design that the widows can use, interact with and emerge from or hide behind as needed.

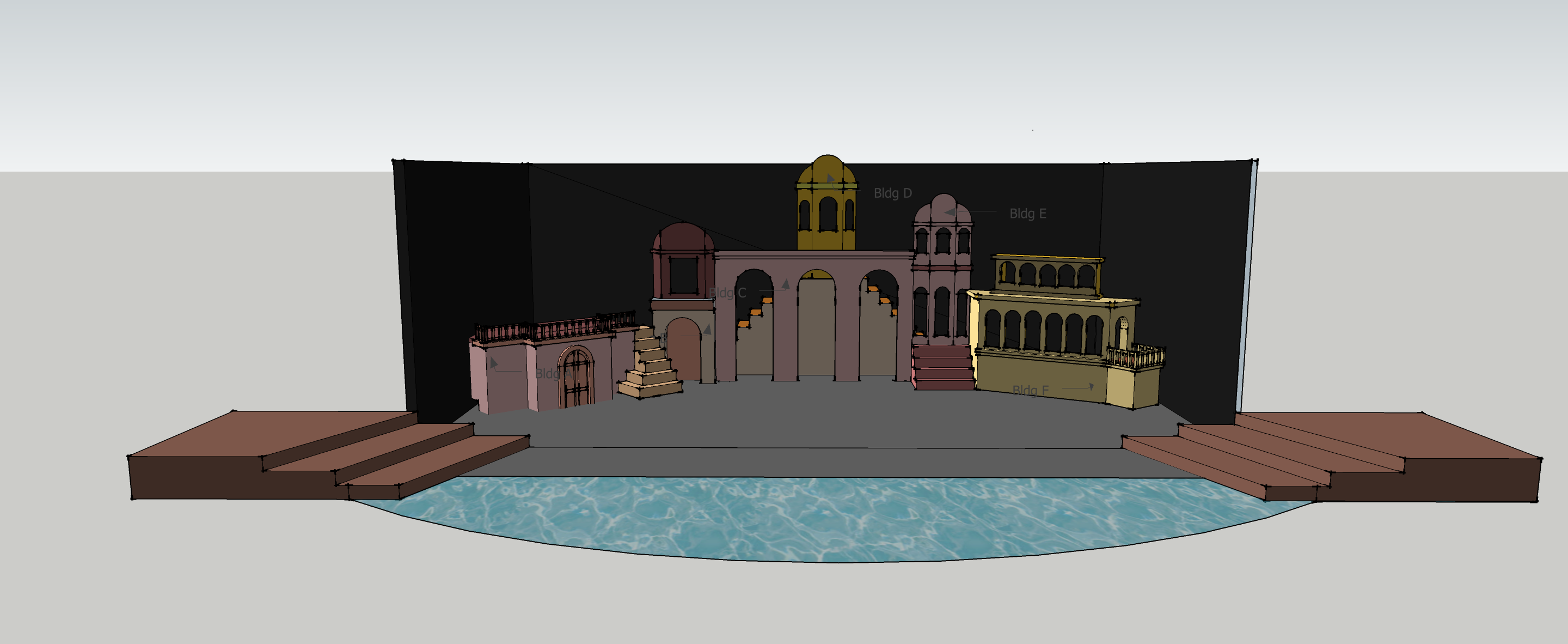

After discussions with the director and sets director, and a few iterations, the final design is created using 3D modeling software and CAD.

I create a design document with detailed notes, dimensions, colors and reference pictures for each piece we need to build. We build the wooden structures, strong enough to support actors climbing, running and jumping on them. We paint walls and murals and relief-work, create texture and age.

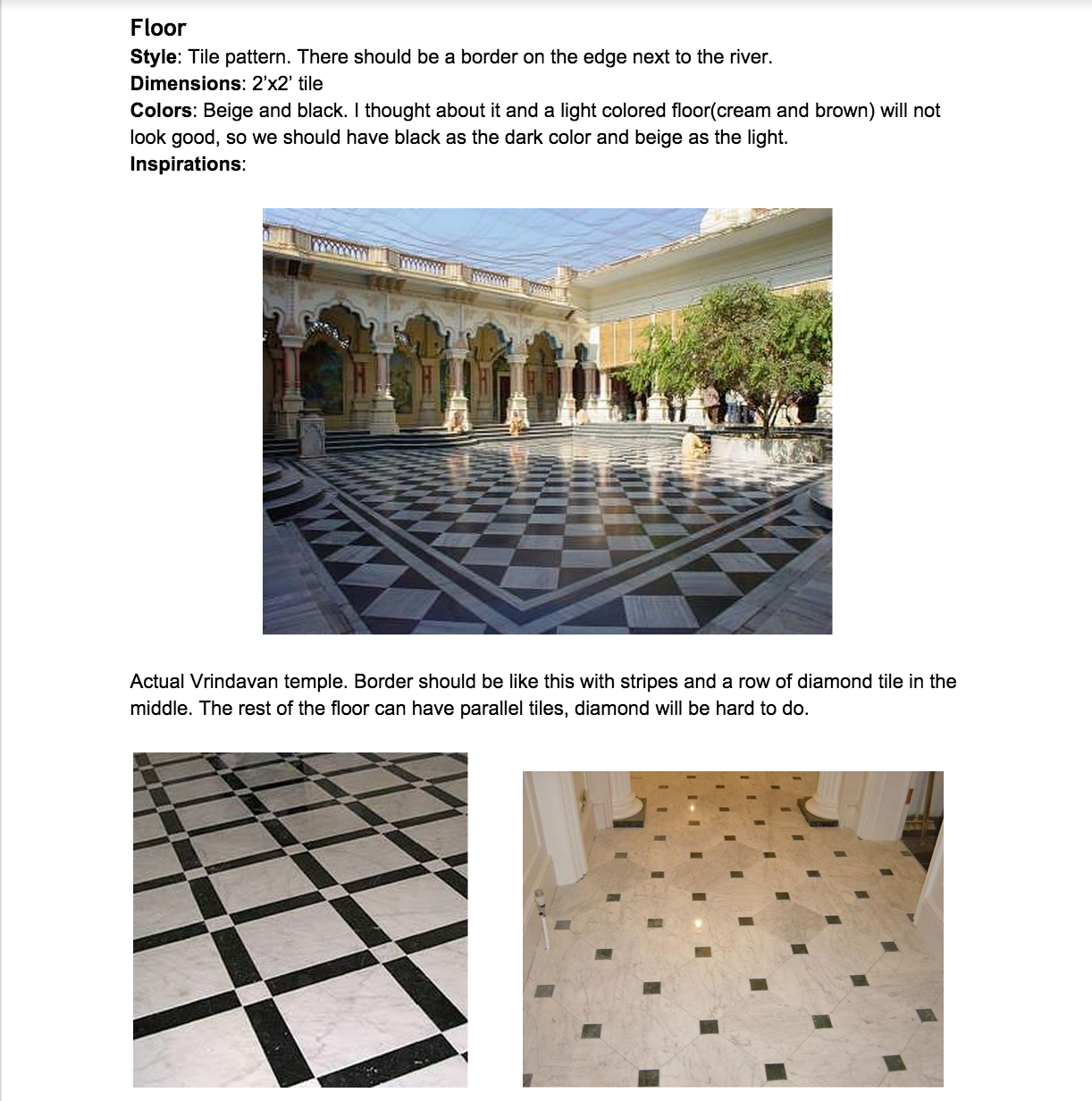

We create black and white tiled marble floors typical of Indian temples and temple towns, my favorite part of the set.

The river Yamuna plays a big part in the story, and without giving away the plot, let me just say that some really special effects are required. The sets team brainstorms and creates a river, beautiful and magical. We don our paint-splotched Naatak work clothes with pride.

The props team creates detailed and beautiful props — a blue Krishna in his basket, protected by the 7-headed Sheshnag, Meera’s veena, a lotus-painted chest containing tokens for the widows, a ceremonial oar, marigold garlands. The costumes we get made in India, and some come from our own and Naatak’s closets. The widows in their bleak white saris, chandan malas and tikas are an antithesis to the dancers in their kaleidoscopic leheriya ghagras and opulent jewelry. The musicians seated on the river ghats look impressive in their large safas (headgear). The stage looks beautiful lit up. The lighting creates dawn and dusk, special lights add dancing waves on the river, diyas twinkle on the window ledges.

And so after three months of designing and building, rehearsals and run-throughs, we are ready. It is Naatak’s 20th year, and 50th production, we have a sold-out opening night. The curtains open, the music swells, and the magic begins.

None of this is permanent. The Janmashthmi jhankis of my childhood were not. The day after Janmashthami, the toys and swing were carefully cleaned and wrapped back up in newspaper, the sawdust swept away. The Naatak stage is created for the three weekends of shows, then we strike down. The set is disassembled, many pieces discarded or recycled, some that can be reused are stored in Naatak House along with the costumes and props. But that does not diminish the euphoria of creation. For some fleeting moments of joy, we poured our hearts into it. The next day we start planning for the next production, and so begins the cycle again.